Photo: Chief Obinna Iyiegbu (Obi Cubana)

By Oghenekevwe Kofi

There’s a phrase that has become the unofficial anthem of Nigeria’s elite: “Money na water.” You see it everywhere—from flashy Instagram posts to party toasts, music lyrics to everyday street banter. It’s a boast, a celebration of wealth so fluid and abundant it might as well be flowing from a golden tap. But in a country where the taps are dry for millions, where people walk miles for water, and hospitals operate without electricity, that same phrase sounds more like mockery than motivation.

Let’s be clear: everyone has a right to enjoy the rewards of their hustle. Whether wealth is earned through years of hard work, inheritance, or the murky waters of “the Nigerian way,” individuals are entitled to spend it as they please.

But the problem is not just the wealth—it’s the performance of it. In a country where 133 million people live in multidimensional poverty, the parading of opulence has become both tone-deaf and dangerous. This is not merely inequality—it is an erosion of empathy.

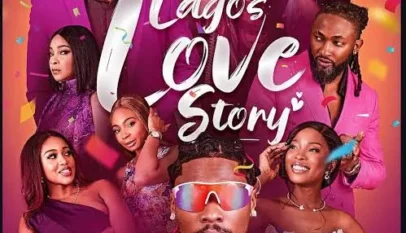

Consider the recent 50th birthday celebration of businessman and socialite Obi Cubana in Abuja. It wasn’t just a party—it was a spectacle. Politicians, celebrities, pastors, and monarchs gathered in a show of wealth that played out like a Netflix series: luxury wristwatches as party souvenirs, stacks of naira notes sprayed into the air like confetti, and champagne poured like water. It trended for weeks. Not for its beauty, but for the surreal disconnect it exposed.

And it’s not the only one. Across the country, lavish weddings, funerals, and traditional festivals have become battlegrounds for status. Some weddings are rumoured to cost upwards of ₦500 million, with private jets, foreign performers, and even drones delivering engagement rings. Pastors host birthday banquets with the kind of budget some local governments can’t even boast. Traditional rulers stage cultural festivals with convoys of luxury SUVS longer than the streets they drive on.

Yet, beyond the tinted glass and red carpets, reality bites hard.

- Over 70% of Nigerians do not have access to basic sanitation facilities, according to UNICEF. Open defecation remains a major health hazard, especially in rural communities.

- Only 57% of Nigerians have access to safe drinking water. In some northern states like Jigawa and Yobe, access drops below 30%.

- Nigeria has one of the highest out-of-school populations in the world, with over 20 million children not attending school.

- Public healthcare is in crisis: only 43% of health facilities have access to clean water, and less than 20% are adequately equipped to handle emergencies.

- Electricity access hovers around 55% nationally, but even those connected endure frequent blackouts—averaging 32 power outages per month, according to the World Bank.

- An estimated 95 million Nigerians live without access to electricity altogether, forcing reliance on expensive generators or kerosene lanterns.

- Over 60% of urban residents live in informal settlements or slums, with little to no access to infrastructure. In Lagos alone, over 300 slum communities struggle daily without water, drainage, healthcare, or proper shelter.

In contrast to this bleak landscape, the elite continue to splash obscene sums on temporary pleasures. But we must ask: What kind of society glorifies excess while ignoring its people’s most basic needs?

This is not an attack on wealth—it is a critique of values. True prestige should not be measured by how much you can flaunt but by how much you can fix. Influence must come with responsibility. And success must mean more than self-indulgence.

Imagine if just one high-profile event rechanneled 10% of its budget to a local school, a borehole project, or a maternity clinic. Imagine if Nigeria’s wealthy elite collaborated to fix roads, digitise public schools, or end child malnutrition, which still affects over 30% of children under five.

Yes, money na water—but let that water flow to quench the thirst of millions, not just rinse Rolexes in champagne.

Until we redefine success as collective elevation, not individual exhibition, we will remain a country where wealth is worshipped and poverty is normalised.

And that, perhaps, is the most dangerous illusion of all.

“Money na water”? Perhaps. But let it be water that gives life, not just one that flows into champagne bottles and ice buckets.