By Imarievwe Osakwe, Guest Writer

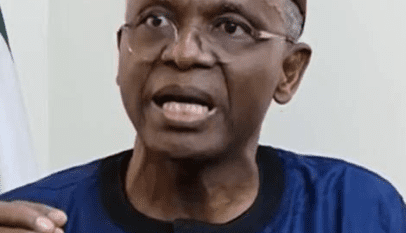

A frightening number can win more attention than a thousand correct words. That is why former Transportation Minister Rotimi Amaechi’s claim, that Nigeria’s new tax law will automatically seize 25 percent of private payments, gained instant traction. It is simple, alarming, and politically useful. It is also wrong. Not slightly wrong, but structurally and factually wrong.

To understand why, you have to look at what the new tax framework actually contains. When you do, the claim collapses.

Amaechi said that if someone pays ₦100 million for materials, ₦25 million will automatically leave the recipient’s account under the new law. That statement assumes three things: that the law authorizes automatic transaction debits, that it taxes gross receipts rather than assessed income, and that the rate is a flat 25 percent across ordinary commercial payments. None of those assumptions is supported by the law.

Nigeria’s tax reform package, which took effect January 1, 2026, is primarily a consolidation and modernization exercise. It merges dozens of overlapping taxes into a more unified structure, renames and restructures the federal tax authority into the Nigeria Revenue Service, expands digital reporting requirements, and updates rules around emerging asset classes such as digital transactions. Its purpose is administrative clarity and broader compliance: it is not instant extraction from bank inflows.

Under the framework, taxes are triggered by taxable income categories, not by the mere arrival of money in an account. The law maintains the core architecture used globally: companies are taxed on profits, not turnover; individuals are taxed on chargeable income, not gross receipts; value-added tax applies to eligible goods and services, not every transfer of funds; and sector-specific rules define when withholding applies — and at what rate.

Take company taxation. Businesses do not pay tax on every naira they receive. They calculate revenue, subtract allowable expenses, such as cost of materials, operating costs, depreciation allowances, and other recognized deductions, and are taxed on profit. A materials supplier paid ₦100 million is not taxed on ₦100 million. The supplier is taxed on margin after cost. No automatic 25 percent debit exists in that chain, as Amaechi falsely claimed.

Consider value-added tax. VAT applies to eligible goods and services at the statutory rate and is charged at point of sale where applicable. It is collected by the seller and remitted — not swept from the seller’s account by government software after payment lands. Many categories remain exempt or zero-rated. Residential rent, basic food items, medical services, and education services are typically outside VAT scope. Again, no automatic quarter-cut exists.

Withholding tax, often confused in public debate, is neither new nor universal. It applies only to specified commercial transactions between defined parties, at rates far below 25 percent, and functions as an advance credit against final tax liability. It is later reconciled. It is not a final tax and not applied to every payment. Calling this a blanket 25 percent automatic deduction is like calling a traffic checkpoint a property seizure.

Personal income tax remains banded by income levels. Lower earners fall into lower brackets or below taxable thresholds altogether. The reform did not convert personal income tax into a flat 25 percent sweep on incoming funds. That would not be reform, it would be confiscation, and it is nowhere in the statute.

Digital asset and cross-border transaction provisions were added to close emerging gaps, but they too operate through classification and reporting — not instant extraction.

So what exactly would have to be true for Amaechi’s claim to be accurate? The law would need a clause authorizing automatic percentage debits on all incoming payments regardless of expense structure, income classification, or taxpayer status. No such clause exists. No implementing regulation suggests it. No tax authority circular describes it. No compliance manual anticipates it.

Amaechi is experienced enough to know how tax systems work. He has governed a state, chaired a governors’ forum, and run a major federal ministry. That makes the distortion more politically significant, not less.

His political journey provides context. Once a central figure in the ruling coalition, he later fell out of alignment after losing a presidential primary contest and has since repositioned within the opposition ahead of the next election cycle. Politicians who move from power center to opposition flank often sharpen their rhetoric. Policies once defended become policies framed as threats. That is politics. But when rhetoric replaces mechanism, it becomes misinformation.

There are real debates worth having about the tax reform — whether compliance burdens will strain small businesses, whether enforcement capacity is ready, whether timing aligns with economic conditions, whether indirect price effects will hit consumers. Those are legitimate policy arguments. They stand on their own. They do not need invented deduction rules to be persuasive.

Vendetta politics, however, thrives on dramatization. Frame the reform as hidden punishment. Attach it to electoral timing. Add a memorable percentage. The message sticks, even if the law says otherwise.

The cost of such distortion is not partisan, it is civic. Citizens make financial decisions based on false assumptions. Businesses delay investments unnecessarily. Public debate drifts from text to rumor. Corrections sound defensive even when they are factual.

Democracy does not require voters to trust government. It does require that critics describe laws accurately when attacking them.

The new tax law should be judged on what it contains: consolidation, modernization, clarified categories, digital reporting, profit-based assessment, and not on a phantom 25 percent auto-seizure rule that does not exist. When a claim contradicts the basic mechanics of taxation itself, the burden is not on citizens to panic, it is on the claimant to prove.

Amaechi cannot, because the provision isn’t there.