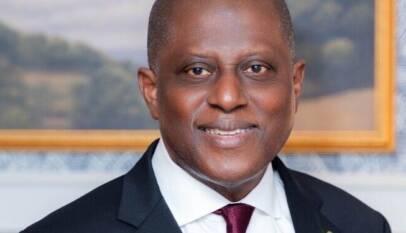

Photo: Pastor Chris Okafor and Doris Ogala, who accused him of ‘sampling’ and dumping her

By Didimoko A. Didimoko

For decades, Nigeria’s Pentecostal revival has been driven by powerful men whose influence stretches far beyond the pulpit. They command vast congregations, control enormous financial resources and shape the private lives of millions of followers. Yet, behind the language of holiness and moral authority, a recurring pattern has emerged: some of the most damaging revelations about prominent pastors have come not from police investigations or church tribunals, but from women who were once their closest confidants – lovers, protégées, wives or spiritual daughters.

These disclosures have not only exposed alleged sexual misconduct but have also lifted the veil on how unchecked spiritual power, secrecy and celebrity culture intersect within modern Nigerian Christianity.

Biodun Fatoyinbo of COZA

One of the most consequential cases involved Biodun Fatoyinbo, founder of the Commonwealth of Zion Assembly. In 2019, Busola Dakolo, wife of songster, Timi Dakolo, accused Fatoyinbo of raping her in the late 1990s when she was a teenager and a member of his church. She alleged that he used spiritual authority, isolation and fear to silence her for years. Fatoyinbo denied the allegation, and prosecutors later said there was insufficient evidence to pursue charges, citing the statute of limitations and lack of corroboration. Yet the case triggered nationwide protests, forced a public reckoning within charismatic churches and permanently altered how many Nigerians viewed pastoral power and sexual vulnerability.

Apostle Johnson Suleman – Omega Fire Ministries:

Unlike Fatoyinbo’s case, which centred on a single, detailed accusation, allegations against Johnson Suleman have surfaced repeatedly over time. Multiple women, including popular Nollywood actor, some publicly identified, others anonymous, have accused the Omega Fire Ministries founder of maintaining secret sexual relationships with them. In 2017, a Canada-based woman released alleged call logs and travel details claiming an affair. Others later made similar claims, alleging that encounters were cloaked in prophetic language or spiritual mentorship. Suleman has consistently denied all allegations, framing them as blackmail, conspiracy or attacks on his ministry. No criminal conviction has followed, but the recurrence of similar accusations has kept scrutiny alive.

Joshua Iginla: Champions Royal Assembly

In a rare moment of admission, Joshua Iginla, founder of Champions Royal Assembly in Abuja, publicly acknowledged committing adultery with a church member in 2019. The admission came after his wife accused him of betrayal and emotional abuse. Iginla stepped down temporarily, apologised and later returned to ministry, arguing that repentance and forgiveness entitled him to restoration. His case sparked intense debate within Christian circles over whether moral failure should permanently disqualify spiritual leadership or be treated as a personal lapse.

Timothy Omotoso

The most severe legal consequences emerged outside Nigeria. Timothy Omotoso, a Nigerian pastor operating in South Africa, was arrested in 2017 and in 2023 convicted on multiple counts including sexual assault, racketeering and human trafficking. Prosecutors said Omotoso used religion, prophecy and coercion to sexually exploit young female congregants, some of whom were groomed under the guise of spiritual training. His conviction marked one of the few cases where allegations against a high-profile pastor translated into a prison sentence, underscoring how rare legal accountability remains in this sphere.

Chris Okafor

More recently, public attention turned to Chris Okafor, after Nollywood actress Doris Ogala accused him of maintaining a secret relationship, promising marriage and later attempting to silence her. Okafor denied the allegations but later issued a public apology during a church service, kneeling before his congregation and admitting to past “mistakes” without confirming specific claims. The carefully worded apology illustrated a common pattern: expressions of remorse framed broadly enough to seek forgiveness while avoiding legal exposure.

Across these cases, a consistent structure emerges. The women involved often describe entering pastors’ lives through church work, counselling sessions or spiritual mentorship. Boundaries blur under the weight of prophecy, obedience and reverence. Silence is maintained through fear—of public shaming, spiritual condemnation or being labelled enemies of God. When relationships collapse or promises fail, exposure becomes the final form of leverage.

Church responses follow predictable lines: denial, spiritualisation of allegations, appeals to forgiveness, or internal “reconciliation” processes that rarely involve independent scrutiny. Congregations are mobilised to defend leaders, while accusers face harassment, lawsuits or character assassination. In many ministries, governance structures are weak or non-existent, leaving founders effectively answerable only to themselves.

Social media has shifted the balance of power. Platforms like X, Instagram and YouTube have stripped churches of narrative control, allowing allegations to spread instantly and forcing leaders into public response before internal mechanisms can contain damage. What was once whispered now trends.

Yet the deeper issue extends beyond individual pastors. These scandals expose systemic flaws in a religious ecosystem built around celebrity leadership, financial opacity and spiritual absolutism. Where pastors are treated as untouchable vessels of divine authority, accountability becomes heresy and consent becomes complicated by fear and reverence.

For Nigeria, where faith remains central to social life, the repeated unmasking of sexual secrets at the altar has fuelled growing cynicism, particularly among younger believers. Some have left organised religion entirely; others demand structural reform, clearer safeguarding policies and independent oversight.

Whether this wave of exposure will lead to lasting change remains uncertain. What is clear is that the most destabilising force confronting Nigeria’s Pentecostal establishment has not been external persecution, but the voices of those who once stood closest to its most powerful men—and chose, finally, to speak.